22. Likelihood Ratio Processes#

Contents

22.1. Overview#

This lecture describes likelihood ratio processes and some of their uses.

We’ll study the same setting that is also used in this lecture on exchangeability.

Among the things that we’ll learn are

How a likelihood ratio process is a key ingredient in frequentist hypothesis testing

How a receiver operator characteristic curve summarizes information about a false alarm probability and power in frequentist hypothesis testing

How a statistician can combine frequentist probabilities of type I and type II errors to form posterior probabilities of mistakes in a model selection or in an individual-classification problem

How to use a Kullback-Leibler divergence to quantify the difference between two probability distributions with the same support

How during World War II the United States Navy devised a decision rule for doing quality control on lots of ammunition, a topic that sets the stage for this lecture

A peculiar property of likelihood ratio processes

Let’s start by importing some Python tools.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

from numba import vectorize, jit

from math import gamma

from scipy.integrate import quad

from scipy.optimize import brentq, minimize_scalar

from scipy.stats import beta as beta_dist

import pandas as pd

from IPython.display import display, Math

import quantecon as qe

22.2. Likelihood Ratio Process#

A nonnegative random variable

Before the beginning of time, nature once and for all decides whether she will draw a sequence of IID draws from either

We will sometimes let

Nature knows which density it permanently draws from, but we the observers do not.

We know both

But we want to know.

To do that, we use observations.

We observe a sequence

We want to use these observations to infer whether nature chose

A likelihood ratio process is a useful tool for this task.

To begin, we define a key component of a likelihood ratio process, namely, the time

We assume that

That means that under the

A likelihood ratio process for sequence

where

Sometimes for shorthand we’ll write

Notice that the likelihood process satisfies the recursion

The likelihood ratio and its logarithm are key tools for making inferences using a classic frequentist approach due to Neyman and Pearson [Neyman and Pearson, 1933].

To help us appreciate how things work, the following Python code evaluates

# Parameters for the two Beta distributions

F_a, F_b = 1, 1

G_a, G_b = 3, 1.2

@vectorize

def p(x, a, b):

"""Beta distribution density function."""

r = gamma(a + b) / (gamma(a) * gamma(b))

return r * x** (a-1) * (1 - x) ** (b-1)

f = jit(lambda x: p(x, F_a, F_b))

g = jit(lambda x: p(x, G_a, G_b))

def create_beta_density(a, b):

"""Create a beta density function with specified parameters."""

return jit(lambda x: p(x, a, b))

def likelihood_ratio(w, f_func, g_func):

"""Compute likelihood ratio for observation(s) w."""

return f_func(w) / g_func(w)

@jit

def simulate_likelihood_ratios(a, b, f_func, g_func, T=50, N=500):

"""

Generate N sets of T observations of the likelihood ratio.

"""

l_arr = np.empty((N, T))

for i in range(N):

for j in range(T):

w = np.random.beta(a, b)

l_arr[i, j] = f_func(w) / g_func(w)

return l_arr

def simulate_sequences(distribution, f_func, g_func,

F_params=(1, 1), G_params=(3, 1.2), T=50, N=500):

"""

Generate N sequences of T observations from specified distribution.

"""

if distribution == 'f':

a, b = F_params

elif distribution == 'g':

a, b = G_params

else:

raise ValueError("distribution must be 'f' or 'g'")

l_arr = simulate_likelihood_ratios(a, b, f_func, g_func, T, N)

l_seq = np.cumprod(l_arr, axis=1)

return l_arr, l_seq

def plot_likelihood_paths(l_seq, title="Likelihood ratio paths",

ylim=None, n_paths=None):

"""Plot likelihood ratio paths."""

N, T = l_seq.shape

n_show = n_paths or min(N, 100)

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

for i in range(n_show):

plt.plot(range(T), l_seq[i, :], color='b', lw=0.8, alpha=0.5)

if ylim:

plt.ylim(ylim)

plt.title(title)

plt.xlabel('t')

plt.ylabel('$L(w^t)$')

plt.show()

22.3. Nature Permanently Draws from Density g#

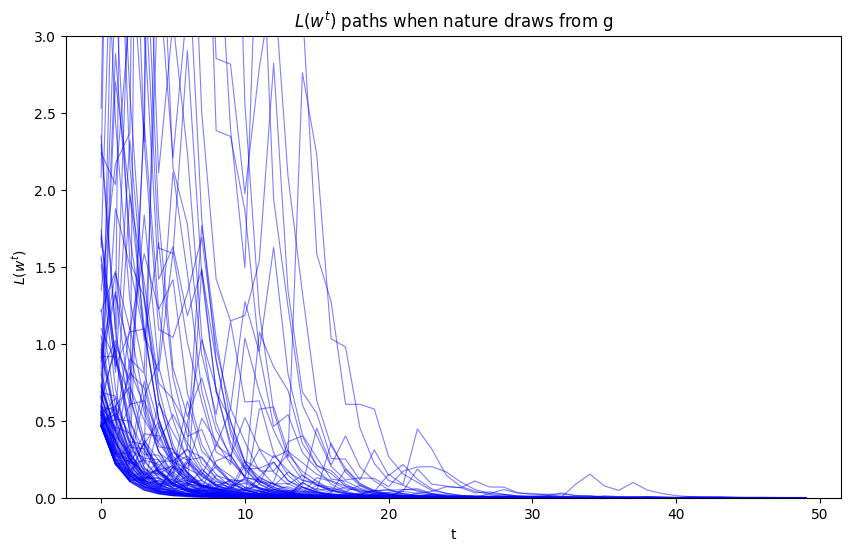

We first simulate the likelihood ratio process when nature permanently

draws from

# Simulate when nature draws from g

l_arr_g, l_seq_g = simulate_sequences('g', f, g, (F_a, F_b), (G_a, G_b))

plot_likelihood_paths(l_seq_g,

title="$L(w^{t})$ paths when nature draws from g",

ylim=[0, 3])

Evidently, as sample length

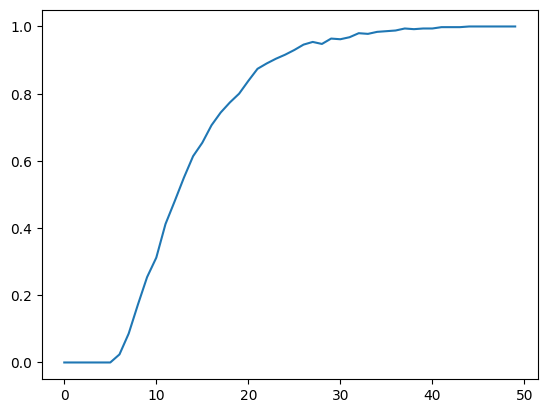

To see this more clearly, we plot over time the fraction of

paths

N, T = l_arr_g.shape

plt.plot(range(T), np.sum(l_seq_g <= 0.01, axis=0) / N)

plt.show()

Despite the evident convergence of most probability mass to a

very small interval near

To verify this assertion, first notice that as mentioned earlier the unconditional mean

which immediately implies

Because

for any

Mathematical induction implies

22.4. Peculiar Property#

How can

The answer is that as

To illustrate this peculiar property, we simulate many paths and

calculate the unconditional mean of

l_arr_g, l_seq_g = simulate_sequences('g',

f, g, (F_a, F_b), (G_a, G_b), N=50000)

It would be useful to use simulations to verify that unconditional means

But it would be too computer-time-consuming for us to do that here simply by applying a standard Monte Carlo simulation approach.

The reason is that the distribution of

Because the probability density in the right tail is close to

We explain the problem in more detail in this lecture.

There we describe an alternative way to compute the mean of a likelihood ratio by computing the mean of a different random variable by sampling from a different probability distribution.

22.5. Nature Permanently Draws from Density f#

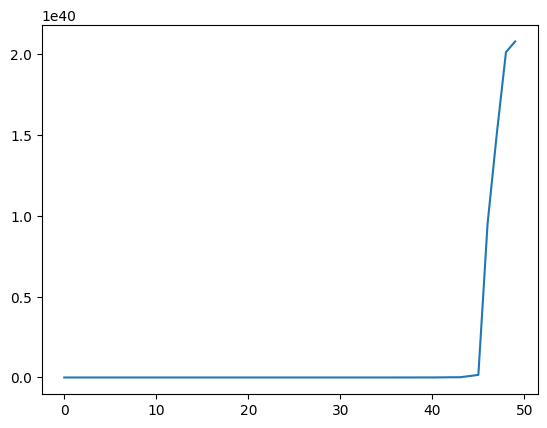

Now suppose that before time

While the mean of the likelihood ratio

To see this, we compute

This in turn implies that the unconditional mean of the likelihood ratio process

Simulations below confirm this conclusion.

Please note the scale of the

# Simulate when nature draws from f

l_arr_f, l_seq_f = simulate_sequences('f', f, g,

(F_a, F_b), (G_a, G_b), N=50000)

N, T = l_arr_f.shape

plt.plot(range(T), np.mean(l_seq_f, axis=0))

plt.show()

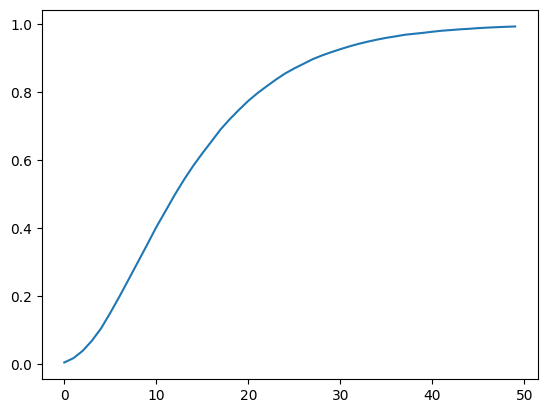

We also plot the probability that

plt.plot(range(T), np.sum(l_seq_f > 10000, axis=0) / N)

plt.show()

22.6. Likelihood Ratio Test#

We now describe how to employ the machinery

of Neyman and Pearson [Neyman and Pearson, 1933] to test the hypothesis that history

Denote

Upon observing a sample

We specify

Null hypothesis

Alternative hypothesis

Neyman and Pearson proved that the best way to test this hypothesis is to use a likelihood ratio test that takes the form:

accept

reject

where

Setting

We’ll discuss consequences of other choices of

This test is best in the sense that it is uniformly most powerful.

To understand what this means, we have to define probabilities of two important events that

allow us to characterize a test associated with a given

threshold

The two probabilities are:

Probability of a Type I error in which we reject

Probability of a Type II error in which we accept

These two probabilities underlie the following two concepts:

Probability of false alarm (= significance level = probability of Type I error):

Probability of detection (= power = 1 minus probability of Type II error):

The Neyman-Pearson Lemma states that among all possible tests, a likelihood ratio test maximizes the probability of detection for a given probability of false alarm.

Another way to say the same thing is that among all possible tests, a likelihood ratio test maximizes power for a given significance level.

We want a small probability of false alarm and a large probability of detection.

With sample size

A troublesome “that’s life” fact is that these two probabilities move in the same direction as we vary the critical value

Without specifying quantitative losses from making Type I and Type II errors, there is little that we can say about how we should trade off probabilities of the two types of mistakes.

We do know that increasing sample size

Below we plot some informative figures that illustrate this.

We also present a classical frequentist method for choosing a sample

size

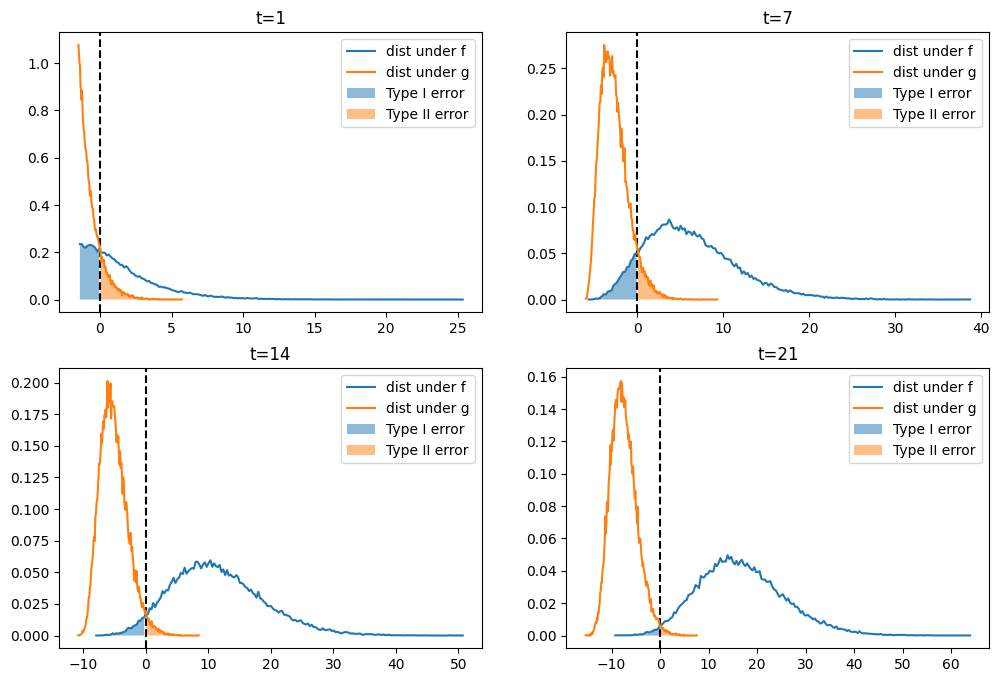

Let’s start with a case in which we fix the threshold

c = 1

Below we plot empirical distributions of logarithms of the cumulative

likelihood ratios simulated above, which are generated by either

Taking logarithms has no effect on calculating the probabilities because the log is a monotonic transformation.

As

This is because most of the probability mass of log

That disparate behavior of log

def plot_log_histograms(l_seq_f, l_seq_g, c=1, time_points=[1, 7, 14, 21]):

"""Plot log likelihood ratio histograms."""

fig, axs = plt.subplots(2, 2, figsize=(12, 8))

for i, t in enumerate(time_points):

nr, nc = i // 2, i % 2

axs[nr, nc].axvline(np.log(c), color="k", ls="--")

hist_f, x_f = np.histogram(np.log(l_seq_f[:, t]), 200, density=True)

hist_g, x_g = np.histogram(np.log(l_seq_g[:, t]), 200, density=True)

axs[nr, nc].plot(x_f[1:], hist_f, label="dist under f")

axs[nr, nc].plot(x_g[1:], hist_g, label="dist under g")

# Fill error regions

for j, (x, hist, label) in enumerate(

zip([x_f, x_g], [hist_f, hist_g],

["Type I error", "Type II error"])):

ind = x[1:] <= np.log(c) if j == 0 else x[1:] > np.log(c)

axs[nr, nc].fill_between(x[1:][ind], hist[ind],

alpha=0.5, label=label)

axs[nr, nc].legend()

axs[nr, nc].set_title(f"t={t}")

plt.show()

plot_log_histograms(l_seq_f, l_seq_g, c=c)

In the above graphs,

the blue areas are related to but not equal to probabilities

the orange areas are related to but not equal to probabilities

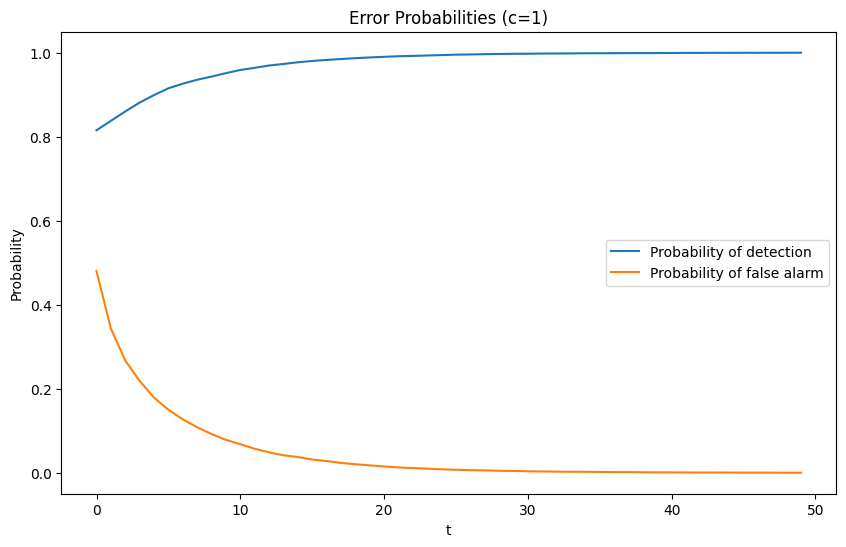

When we hold

the probability of detection monotonically increases with increases in

the probability of a false alarm monotonically decreases with increases in

def compute_error_probabilities(l_seq_f, l_seq_g, c=1):

"""

Compute Type I and Type II error probabilities.

"""

N, T = l_seq_f.shape

# Type I error (false alarm) - reject H0 when true

PFA = np.array([np.sum(l_seq_f[:, t] < c) / N for t in range(T)])

# Type II error - accept H0 when false

beta = np.array([np.sum(l_seq_g[:, t] >= c) / N for t in range(T)])

# Probability of detection (power)

PD = np.array([np.sum(l_seq_g[:, t] < c) / N for t in range(T)])

return {

'alpha': PFA,

'beta': beta,

'PD': PD,

'PFA': PFA

}

def plot_error_probabilities(error_dict, T, c=1, title_suffix=""):

"""Plot error probabilities over time."""

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

plt.plot(range(T), error_dict['PD'], label="Probability of detection")

plt.plot(range(T), error_dict['PFA'], label="Probability of false alarm")

plt.xlabel("t")

plt.ylabel("Probability")

plt.title(f"Error Probabilities (c={c}){title_suffix}")

plt.legend()

plt.show()

error_probs = compute_error_probabilities(l_seq_f, l_seq_g, c=c)

N, T = l_seq_f.shape

plot_error_probabilities(error_probs, T, c)

For a given sample size

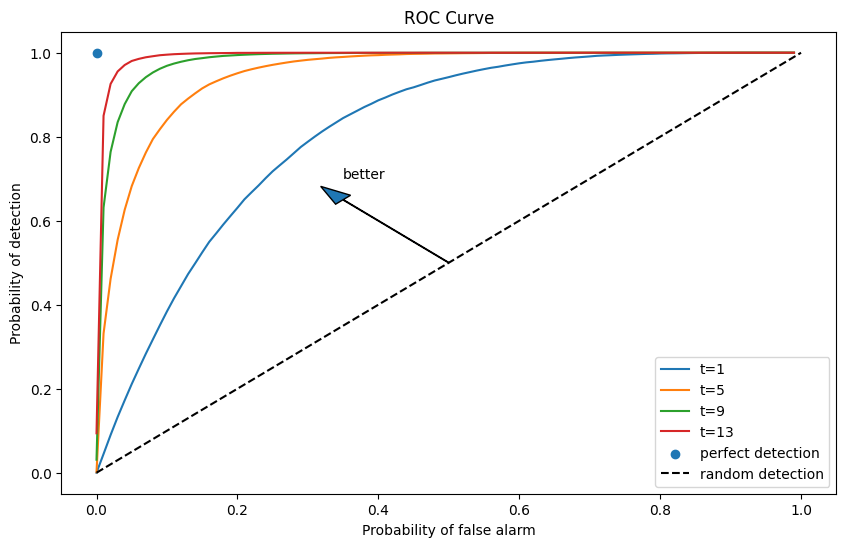

If for a fixed

This produces a receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC curve).

Below, we plot receiver operating characteristic curves for different

sample sizes

def plot_roc_curves(l_seq_f, l_seq_g, t_values=[1, 5, 9, 13], N=None):

"""Plot ROC curves for different sample sizes."""

if N is None:

N = l_seq_f.shape[0]

PFA = np.arange(0, 100, 1)

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

for t in t_values:

percentile = np.percentile(l_seq_f[:, t], PFA)

PD = [np.sum(l_seq_g[:, t] < p) / N for p in percentile]

plt.plot(PFA / 100, PD, label=f"t={t}")

plt.scatter(0, 1, label="perfect detection")

plt.plot([0, 1], [0, 1], color='k', ls='--', label="random detection")

plt.arrow(0.5, 0.5, -0.15, 0.15, head_width=0.03)

plt.text(0.35, 0.7, "better")

plt.xlabel("Probability of false alarm")

plt.ylabel("Probability of detection")

plt.legend()

plt.title("ROC Curve")

plt.show()

plot_roc_curves(l_seq_f, l_seq_g, t_values=range(1, 15, 4), N=N)

Notice that as

For a given sample size

As we increase

As

For a given sample size

It is up to the test designer to trade off probabilities of making the two types of errors.

But we know how to choose the smallest sample size to achieve given targets for the probabilities.

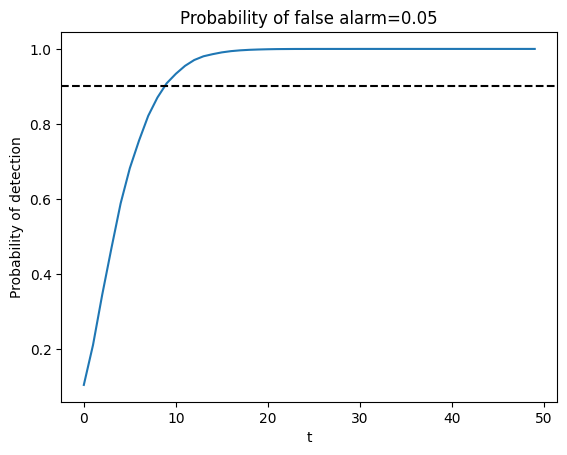

Typically, frequentists aim for a high probability of detection that respects an upper bound on the probability of false alarm.

Below we show an example in which we fix the probability of false alarm at

The required sample size for making a decision is then determined by a

target probability of detection, for example,

PFA = 0.05

PD = np.empty(T)

for t in range(T):

c = np.percentile(l_seq_f[:, t], PFA * 100)

PD[t] = np.sum(l_seq_g[:, t] < c) / N

plt.plot(range(T), PD)

plt.axhline(0.9, color="k", ls="--")

plt.xlabel("t")

plt.ylabel("Probability of detection")

plt.title(f"Probability of false alarm={PFA}")

plt.show()

The United States Navy evidently used a procedure like this to select a sample size

A Navy Captain who had been ordered to perform tests of this kind had doubts about it that he presented to Milton Friedman, as we describe in this lecture.

22.6.1. A third distribution

Now let’s consider a case in which neither

Instead, a third distribution

Let’s study how accumulated likelihood ratios

A key tool here is called Kullback–Leibler divergence we studied in Statistical Divergence Measures.

In our application, we want to measure how much

Two Kullback–Leibler divergences pertinent for us are

Let’s compute the Kullback–Leibler discrepancies using the same code in Statistical Divergence Measures.

def compute_KL(f, g):

"""

Compute KL divergence KL(f, g)

"""

integrand = lambda w: f(w) * np.log(f(w) / g(w))

val, _ = quad(integrand, 1e-5, 1-1e-5)

return val

def compute_KL_h(h, f, g):

"""

Compute KL divergences with respect to reference distribution h

"""

Kf = compute_KL(h, f)

Kg = compute_KL(h, g)

return Kf, Kg

22.6.2. A helpful formula#

There is a mathematical relationship between likelihood ratios and KL divergence.

When data is generated by distribution

where

Equation (22.1) tells us that:

When

When

Let’s verify this using simulation.

In the simulation, we generate multiple paths using Beta distributions

First, we write a function to compute the likelihood ratio process

def compute_likelihood_ratios(sequences, f, g):

"""Compute likelihood ratios and cumulative products."""

l_ratios = f(sequences) / g(sequences)

L_cumulative = np.cumprod(l_ratios, axis=1)

return l_ratios, L_cumulative

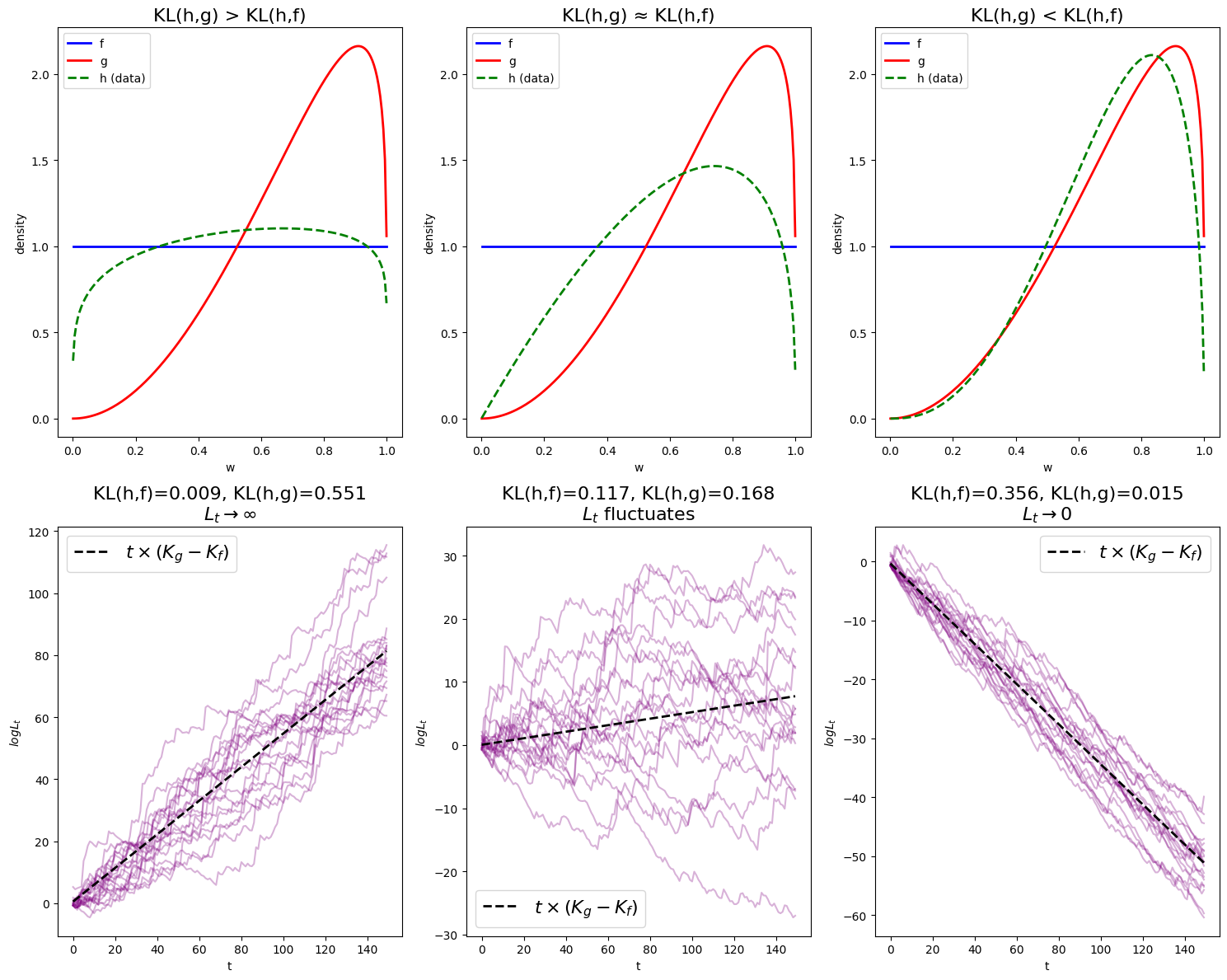

We consider three cases: (1)

Note that

In the first figure,

In the second figure, we still have

In the last figure,

The black dotted line,

These observations align with the theory.

In Heterogeneous Beliefs and Financial Markets, we will see an application of these ideas.

22.7. Hypothesis testing and classification#

This section discusses another application of likelihood ratio processes.

We describe how a statistician can combine frequentist probabilities of type I and type II errors in order to

compute an anticipated frequency of selecting a wrong model based on a sample length

compute an anticipated error rate in a classification problem

We consider a situation in which nature generates data by mixing known densities

We assume that the statistician knows the densities

Below, we’ll set

We assume that

In the simulations below, we specify that

We consider two alternative timing protocols.

Timing protocol 1 is for the model selection problem

Timing protocol 2 is for the individual classification problem

Timing Protocol 1: Nature flips a coin only once at time

Timing Protocol 2. Nature flips a coin often. At each time

Here is Python code that we’ll use to implement timing protocol 1 and 2

def protocol_1(π_minus_1, T, N=1000, F_params=(1, 1), G_params=(3, 1.2)):

"""

Simulate Protocol 1: Nature decides once at t=-1 which model to use.

"""

F_a, F_b = F_params

G_a, G_b = G_params

# Single coin flip for the true model

true_models_F = np.random.rand(N) < π_minus_1

sequences = np.empty((N, T))

n_f = np.sum(true_models_F)

n_g = N - n_f

if n_f > 0:

sequences[true_models_F, :] = np.random.beta(F_a, F_b, (n_f, T))

if n_g > 0:

sequences[~true_models_F, :] = np.random.beta(G_a, G_b, (n_g, T))

return sequences, true_models_F

def protocol_2(π_minus_1, T, N=1000, F_params=(1, 1), G_params=(3, 1.2)):

"""

Simulate Protocol 2: Nature decides at each time step which model to use.

"""

F_a, F_b = F_params

G_a, G_b = G_params

# Coin flips for each time step

true_models_F = np.random.rand(N, T) < π_minus_1

sequences = np.empty((N, T))

n_f = np.sum(true_models_F)

n_g = N * T - n_f

if n_f > 0:

sequences[true_models_F] = np.random.beta(F_a, F_b, n_f)

if n_g > 0:

sequences[~true_models_F] = np.random.beta(G_a, G_b, n_g)

return sequences, true_models_F

Remark: Under timing protocol 2, the

We again deploy a likelihood ratio process with time

The likelihood ratio process for sequence

For shorthand we’ll write

22.7.1. Model selection mistake probability#

We first study a problem that assumes timing protocol 1.

Consider a decision maker who wants to know whether model

The decision makers has observed a sequence

On the basis of that observed sequence, a likelihood ratio test selects model

When model

When model

We can construct a probability that the likelihood ratio selects the wrong model by assigning a Bayesian prior probability of

Now let’s simulate timing protocol 1 and 2 and compute the error probabilities

def compute_protocol_1_errors(π_minus_1, T_max, N_simulations, f_func, g_func,

F_params=(1, 1), G_params=(3, 1.2)):

"""

Compute error probabilities for Protocol 1.

"""

sequences, true_models = protocol_1(

π_minus_1, T_max, N_simulations, F_params, G_params)

l_ratios, L_cumulative = compute_likelihood_ratios(sequences,

f_func, g_func)

T_range = np.arange(1, T_max + 1)

mask_f = true_models

mask_g = ~true_models

L_f = L_cumulative[mask_f, :]

L_g = L_cumulative[mask_g, :]

α_T = np.mean(L_f < 1, axis=0)

β_T = np.mean(L_g >= 1, axis=0)

error_prob = 0.5 * (α_T + β_T)

return {

'T_range': T_range,

'alpha': α_T,

'beta': β_T,

'error_prob': error_prob,

'L_cumulative': L_cumulative,

'true_models': true_models

}

def compute_protocol_2_errors(π_minus_1, T_max, N_simulations, f_func, g_func,

F_params=(1, 1), G_params=(3, 1.2)):

"""

Compute error probabilities for Protocol 2.

"""

sequences, true_models = protocol_2(π_minus_1,

T_max, N_simulations, F_params, G_params)

l_ratios, _ = compute_likelihood_ratios(sequences, f_func, g_func)

T_range = np.arange(1, T_max + 1)

accuracy = np.empty(T_max)

for t in range(T_max):

predictions = (l_ratios[:, t] >= 1)

actual = true_models[:, t]

accuracy[t] = np.mean(predictions == actual)

return {

'T_range': T_range,

'accuracy': accuracy,

'l_ratios': l_ratios,

'true_models': true_models

}

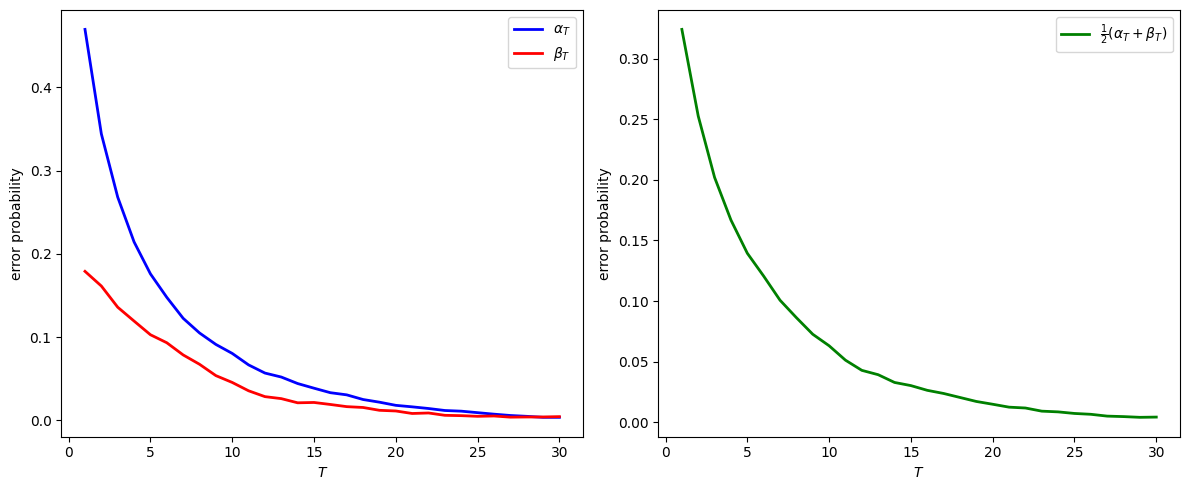

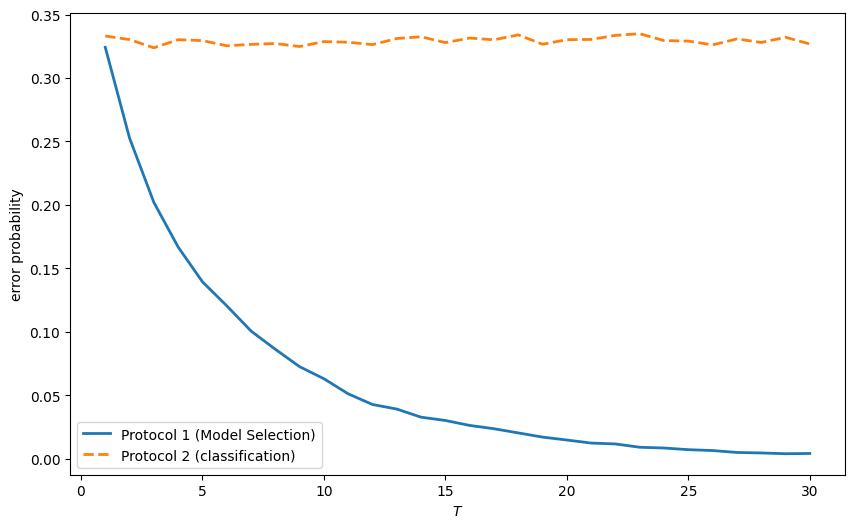

The following code visualizes the error probabilities for timing protocol 1 and 2

At T=30:

α_30 = 0.0038

β_30 = 0.0046

Model selection error probability = 0.0042

Notice how the model selection error probability approaches zero as

22.7.2. Classification#

We now consider a problem that assumes timing protocol 2.

A decision maker wants to classify components of an observed sequence

The decision maker uses the following classification rule:

Under this rule, the expected misclassification rate is

where

Since for each

root = brentq(lambda w: f(w) / g(w) - 1, 0.001, 0.999)

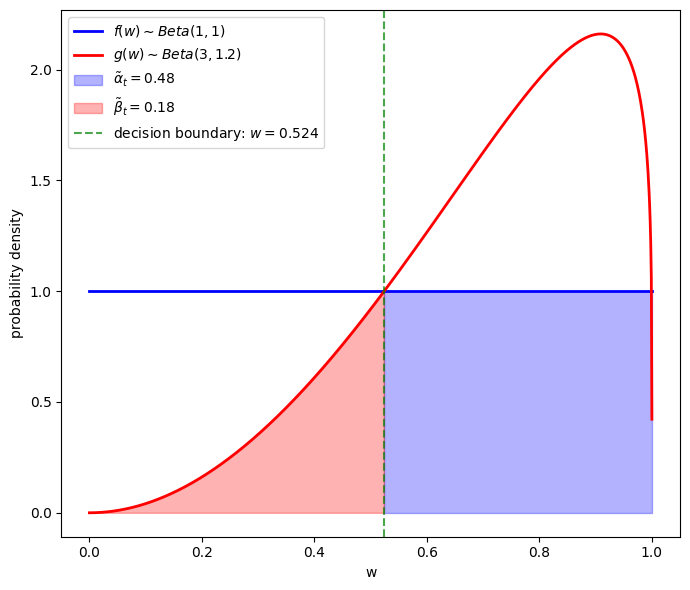

we can plot the distributions of

To the left of the green vertical line

The shaded orange area equals

To the right of the green vertical line

The shaded blue area equals

This gives us clues about how to compute the theoretical classification error probability

# Compute theoretical tilde α_t and tilde β_t

def α_integrand(w):

"""Integrand for tilde α_t = P(l_t < 1 | f)"""

return f(w) if f(w) / g(w) < 1 else 0

def β_integrand(w):

"""Integrand for tilde β_t = P(l_t >= 1 | g)"""

return g(w) if f(w) / g(w) >= 1 else 0

# Compute the integrals

α_theory, _ = quad(α_integrand, 0, 1, limit=100)

β_theory, _ = quad(β_integrand, 0, 1, limit=100)

theory_error = 0.5 * (α_theory + β_theory)

print(f"theoretical tilde α_t = {α_theory:.4f}")

print(f"theoretical tilde β_t = {β_theory:.4f}")

print(f"theoretical classification error probability = {theory_error:.4f}")

theoretical tilde α_t = 0.4752

theoretical tilde β_t = 0.1836

theoretical classification error probability = 0.3294

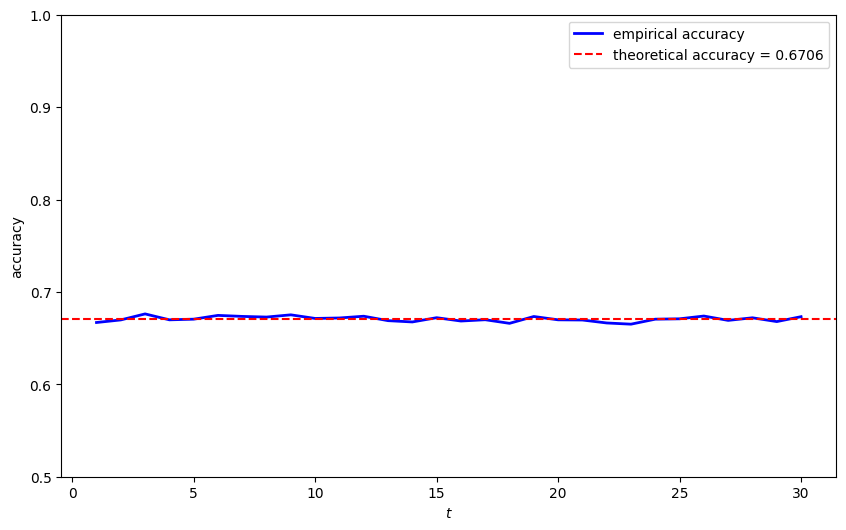

Now we simulate timing protocol 2 and compute the classification error probability.

In the next cell, we also compare the theoretical classification accuracy to the empirical classification accuracy

# Analyze Protocol 2

result_p2 = analyze_protocol_2(π_minus_1, T_max, N_simulations, f, g,

theory_error, (F_a, F_b), (G_a, G_b))

Let’s watch decisions made by the two timing protocols as more and more observations accrue.

# Compare both protocols

compare_protocols(result_p1, result_p2)

From the figure above, we can see:

For both timing protocols, the error probability starts at the same level, subject to a little randomness.

For timing protocol 1, the error probability decreases as the sample size increases because we are making just one decision – i.e., selecting whether

For timing protocol 2, the error probability remains constant because we are making many decisions – one classification decision for each observation.

Remark: Think about how laws of large numbers are applied to compute error probabilities for the model selection problem and the classification problem.

22.7.3. Error probability and divergence measures#

A plausible guess is that the ability of a likelihood ratio to distinguish distributions

We have learnt some measures of “difference” between distributions in Statistical Divergence Measures.

Let’s now study two more measures of “difference” between distributions that are useful in the context of model selection and classification.

Recall that Chernoff entropy between probability densities

An upper bound on model selection error probability is

Let’s compute Chernoff entropy numerically with some Python code

def chernoff_integrand(ϕ, f, g):

"""

Compute the integrand for Chernoff entropy

"""

def integrand(w):

return f(w)**ϕ * g(w)**(1-ϕ)

result, _ = quad(integrand, 1e-5, 1-1e-5)

return result

def compute_chernoff_entropy(f, g):

"""

Compute Chernoff entropy C(f,g)

"""

def objective(ϕ):

return chernoff_integrand(ϕ, f, g)

# Find the minimum over ϕ in (0,1)

result = minimize_scalar(objective,

bounds=(1e-5, 1-1e-5),

method='bounded')

min_value = result.fun

ϕ_optimal = result.x

chernoff_entropy = -np.log(min_value)

return chernoff_entropy, ϕ_optimal

C_fg, ϕ_optimal = compute_chernoff_entropy(f, g)

print(f"Chernoff entropy C(f,g) = {C_fg:.4f}")

print(f"Optimal ϕ = {ϕ_optimal:.4f}")

Chernoff entropy C(f,g) = 0.1212

Optimal ϕ = 0.5969

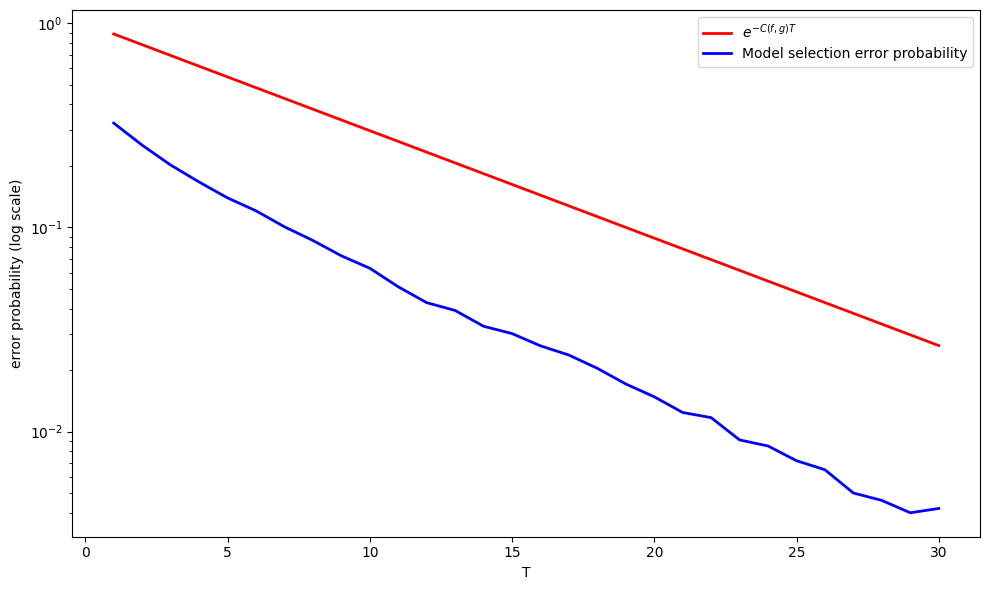

Now let’s examine how

T_range = np.arange(1, T_max+1)

chernoff_bound = np.exp(-C_fg * T_range)

# Plot comparison

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 6))

ax.semilogy(T_range, chernoff_bound, 'r-', linewidth=2,

label=f'$e^{{-C(f,g)T}}$')

ax.semilogy(T_range, result_p1['error_prob'], 'b-', linewidth=2,

label='Model selection error probability')

ax.set_xlabel('T')

ax.set_ylabel('error probability (log scale)')

ax.legend()

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Evidently,

In {doc}divergence_measures`, we also studied Jensen-Shannon divergence as

a symmetric measure of distance between distributions.

We can use Jensen-Shannon divergence to measure the distance between distributions

We also compute Jensen-Shannon divergence numerically with some Python code

def compute_JS(f, g):

"""

Compute Jensen-Shannon divergence

"""

def m(w):

return 0.5 * (f(w) + g(w))

js_div = 0.5 * compute_KL(f, m) + 0.5 * compute_KL(g, m)

return js_div

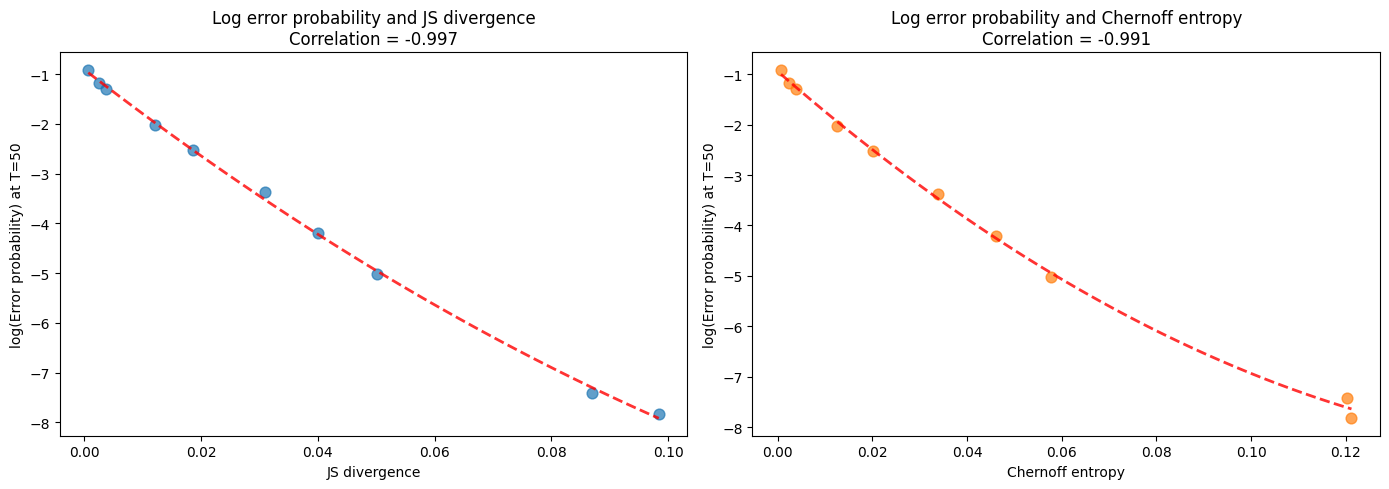

Now let’s return to our guess that the error probability at large sample sizes is related to the Chernoff entropy between two distributions.

We verify this by computing the correlation between the log of the error probability at

In the simulation below, nature draws

Note

Nature does this rather than flipping a fair coin to decide whether to draw from

We use the following pairs of Beta distributions for

distribution_pairs = [

# (f_params, g_params)

((1, 1), (0.1, 0.2)),

((1, 1), (0.3, 0.3)),

((1, 1), (0.3, 0.4)),

((1, 1), (0.5, 0.5)),

((1, 1), (0.7, 0.6)),

((1, 1), (0.9, 0.8)),

((1, 1), (1.1, 1.05)),

((1, 1), (1.2, 1.1)),

((1, 1), (1.5, 1.2)),

((1, 1), (2, 1.5)),

((1, 1), (2.5, 1.8)),

((1, 1), (3, 1.2)),

((1, 1), (4, 1)),

((1, 1), (5, 1))

]

Now let’s run the simmulation

# Parameters for simulation

T_large = 50

N_sims = 5000

N_half = N_sims // 2

# Initialize arrays

n_pairs = len(distribution_pairs)

kl_fg_vals = np.zeros(n_pairs)

kl_gf_vals = np.zeros(n_pairs)

js_vals = np.zeros(n_pairs)

chernoff_vals = np.zeros(n_pairs)

error_probs = np.zeros(n_pairs)

pair_names = []

for i, ((f_a, f_b), (g_a, g_b)) in enumerate(distribution_pairs):

# Create density functions

f = jit(lambda x, a=f_a, b=f_b: p(x, a, b))

g = jit(lambda x, a=g_a, b=g_b: p(x, a, b))

# Compute divergence measures

kl_fg_vals[i] = compute_KL(f, g)

kl_gf_vals[i] = compute_KL(g, f)

js_vals[i] = compute_JS(f, g)

chernoff_vals[i], _ = compute_chernoff_entropy(f, g)

# Generate samples

sequences_f = np.random.beta(f_a, f_b, (N_half, T_large))

sequences_g = np.random.beta(g_a, g_b, (N_half, T_large))

# Compute likelihood ratios and cumulative products

_, L_cumulative_f = compute_likelihood_ratios(sequences_f, f, g)

_, L_cumulative_g = compute_likelihood_ratios(sequences_g, f, g)

# Get final values

L_cumulative_f = L_cumulative_f[:, -1]

L_cumulative_g = L_cumulative_g[:, -1]

# Calculate error probabilities

error_probs[i] = 0.5 * (np.mean(L_cumulative_f < 1) +

np.mean(L_cumulative_g >= 1))

pair_names.append(f"Beta({f_a},{f_b}) and Beta({g_a},{g_b})")

cor_data = {

'kl_fg': kl_fg_vals,

'kl_gf': kl_gf_vals,

'js': js_vals,

'chernoff': chernoff_vals,

'error_prob': error_probs,

'names': pair_names,

'T': T_large}

Now let’s visualize the correlations

Evidently, Chernoff entropy and Jensen-Shannon entropy each covary tightly with the model selection error probability.

We’ll encounter related ideas in A Problem that Stumped Milton Friedman very soon.

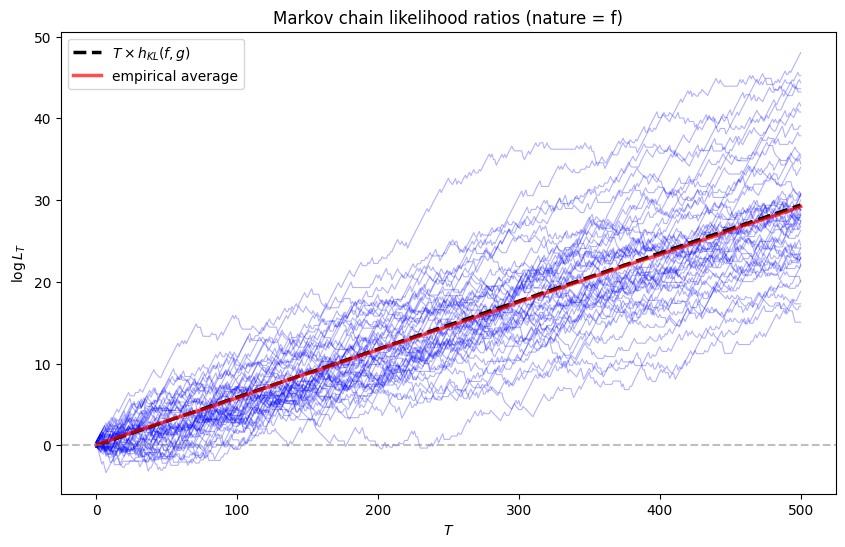

22.8. Markov chains#

Let’s now look at a likelihood ratio process for a sequence of random variables that is not independently and identically distributed.

Here we assume that the sequence is generated by a Markov chain on a finite state space.

We consider two

We assume that nature samples from chain

For a sample path

The likelihood process under model

Hence,

The log-likelihood ratio is

22.8.1. KL divergence rate#

By the ergodic theorem for irreducible, aperiodic Markov chains, we have

where

Therefore,

Taking the limit as

The first term:

The second term:

Define the KL divergence rate as

where

By the ergodic theorem, we have

Taking expectations and using the dominated convergence theorem, we obtain

Here we invite readers to pause and compare this result with (22.1).

Let’s confirm this in the simulation below.

22.8.2. Simulations#

Let’s implement simulations to illustrate these concepts with a three-state Markov chain.

We start by writing functions to compute the stationary distribution and the KL divergence rate for Markov chain models.

Now let’s create an example with two different 3-state Markov chains.

We are now ready to simulate paths and visualize how likelihood ratios evolve.

We verify

# Define example Markov chain transition matrices

P_f = np.array([[0.7, 0.2, 0.1],

[0.3, 0.5, 0.2],

[0.1, 0.3, 0.6]])

P_g = np.array([[0.5, 0.3, 0.2],

[0.2, 0.6, 0.2],

[0.2, 0.2, 0.6]])

markov_results = analyze_markov_chains(P_f, P_g)

Stationary distribution (f): [0.41176471 0.32352941 0.26470588]

Stationary distribution (g): [0.28571429 0.38095238 0.33333333]

KL divergence rate h(f, g): 0.0588

KL divergence rate h(g, f): 0.0563

22.10. Exercises#

Exercise 22.1

Consider the setting where nature generates data from a third density

Let

Show that:

with finite

Hint: Start by expressing

Solution to Exercise 22.1

Since

Taking the expectation under

Since the

where

Therefore

Now, from the definition of Kullback-Leibler divergence

This gives us

Similarly

Substituting back

Exercise 22.2

Building on Exercise 22.1, use the result to explain what happens to

When

When

Relate your answer to the simulation results shown in this section.

Solution to Exercise 22.2

From Exercise 22.1, we know that:

Case 1: When

Here,

By the Law of Large Numbers,

Therefore

Case 2: When

Here,

Therefore by similar reasoning